Chinese Religon That Doesnt Eat Beef

The food choices of Jains are based on the value of Ahimsa (non-violence), which ways Jains prefer food that inflicts the least corporeality of violence.

Jain vegetarianism is good by the followers of Jain culture and philosophy. It is one of the most rigorous forms of spiritually motivated nutrition on the Indian subcontinent and beyond. The Jain cuisine is completely lacto-vegetarian and likewise excludes root and hush-hush vegetables such as potato, garlic, onion etc., to prevent injuring minor insects and microorganisms; and also to preclude the entire plant getting uprooted and killed. It is practised by Jain ascetics and lay Jains.[1]

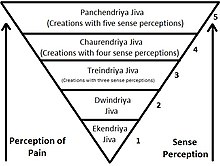

There have been calls within the Jain community to finish the consumption of dairy equally well considering common practices in almost dairies of all sizes are extremely cruel. They consist of impregnating a female animal against her consent repeatedly, separating, selling and even sending the male calves for slaughter, and eventually sending the female to slaughter when her trunk cannot have whatever more pregnancies. The objections to the eating of meat, fish and eggs are besides based on the principle of non-violence (ahimsa, figuratively "non-injuring"). Every human activity by which a person directly or indirectly supports killing or injury is seen as human activity of violence (himsa), which creates harmful reaction karma. The aim of ahimsa is to prevent the accumulation of such karma.[2] [3] The extent to which this intention is put into upshot varies greatly among Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. Jains believe nonviolence is the almost essential religious duty for everyone (ahinsā paramo dharmaḥ, a statement often inscribed on Jain temples).[4] [v] [6] Information technology is an indispensable condition for liberation from the bike of reincarnation,[7] which is the ultimate goal of all Jain activities. Jains share this goal with Hindus and Buddhists, but their arroyo is particularly rigorous and comprehensive. Their scrupulous and thorough way of applying nonviolence to everyday activities, and especially to nutrient, shapes their entire lives and is the well-nigh significant authentication of Jain identity.[8] [9] [10] [11] A side effect of this strict discipline is the exercise of asceticism, which is strongly encouraged in Jainism for lay people too as for monks and nuns.[12] [13] [14] Out of the 5 types of living beings, a householder is forbidden to kill, or destroy, intentionally, all except the lowest (the 1 sensed, such as vegetables, herbs, cereals, etc., which are endowed with merely the sense of touch on).[15]

Do [edit]

For Jains, vegetarianism is mandatory. In 2021 information technology was found that 92% of self-identified Jains in India adhered to some blazon of vegetarian diet and another 5% seem to endeavour to follow a mostly vegetarian diet by abnegation from eating certain kinds of meat and/or abnegation from eating meat on specific days.[16] In the Jain context, Vegetarianism excludes all creature products except dairy products. Food is restricted to that originating from plants, since plants accept only one sense ('ekindriya') and are the least developed form of life, and dairy products. Food that contains fifty-fifty the smallest particles of the bodies of dead animals or eggs is unacceptable.[17] [xviii] Some Jain scholars and activists support veganism, every bit they believe the mod commercialised product of dairy products involves violence confronting farm animals.[19] [20] [21] In ancient times, dairy animals were well cared for and not killed.[22] According to Jain texts, a śrāvaka (householder) should not consume the four maha-vigai (the four perversions) - wine, flesh, butter and honey; and the five udumbara fruits (the 5 udumbara copse are Gular, Anjeera, Banyan, Peepal, and Pakar, all belonging to the fig class). Lastly, Jains should not consume whatever foods or drinks that have animal products or beast flesh. A common misconception is that Jains cannot eat animal-shaped foods or products. As long every bit the foods do non contain animal products or animal flesh, animal shaped foods can be consumed without the fear of committing a sin.[23] [24]

Jains get out of their way so as not to hurt fifty-fifty pocket-sized insects and other tiny animals,[25] [26] [27] [28] because they believe that impairment caused by abandon is every bit reprehensible every bit impairment caused by deliberate action.[29] [30] [31] [32] [33] Hence they accept dandy pains to make certain that no minuscule animals are injured by the preparation of their meals and in the process of eating and drinking.[34] [35]

Traditionally Jains have been prohibited from drinking unfiltered water. In the past, when stepwells were used for the water source, the cloth used for filtering was reversed, and some filtered water poured over it to return the organisms to the original torso of water. This practice of jivani or bilchavani is no longer possible because of the use of pipes for water supply. Modern Jains may also filter tap h2o in the traditional fashion and a few continue to follow the filtering procedure fifty-fifty with commercial mineral or bottled drinking water.

Jains make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life equally far as possible. Jains but take such violence in every bit much equally it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants.[36] [37] [38] Strict Jains do not swallow root vegetables such as potatoes, onions, roots and tubers as they are considered ananthkay.[24] Ananthkay means one body, but containing infinite lives. A root vegetable such as tater, though from the looks of information technology is one article, is said to contain space lives in it. Also, tiny life forms are injured when the plant is pulled up and considering the bulb is seen as a living existence, as it is able to sprout.[39] [40] [41] Besides, consumption of most root vegetables involves uprooting and killing the entire found, whereas consumption of about terrestrial vegetables does not kill the found (it lives on after plucking the vegetables or it was seasonally supposed to wither abroad anyway). Among Indian Jains, 67% study that they abjure from eating root vegetables.[16] Green vegetables and fruits comprise uncountable lives. Dry beans, lentils, cereals, nuts and seeds contain a countable number of lives and their consumption results in the least destruction of life.

Mushrooms, fungi and yeasts are forbidden because they grow in unhygienic environments and may harbour other life forms.[ commendation needed ]

Honey is forbidden, as its collection would amount to violence against the bees.[35] [42] [43]

Jain texts declare that a śrāvaka (householder) should not cook or eat at night. According to Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya:

And, how can ane who eats nutrient without the lite of the sun, albeit a lamp may have been lighted, avoid hiṃsā of minute beings which become into food?

— Puruşārthasiddhyupāya (133)[44]

Strict Jains do not swallow food that has been stored overnight, as it possesses a higher concentration of micro-organisms (for example, bacteria, yeast etc.) as compared to food prepared and consumed the aforementioned day. Hence, they do not consume yoghurt or dhokla and idli concoction unless they have been freshly set on the aforementioned solar day.

During certain days of the month and on important religious days such as Paryushana and 'Ayambil', strict Jains avert eating green leafy vegetables along with the usual restrictions on root vegetables.

Jains do not consume fermented foods (beer, wine and other alcohols) to avoid killing of a large number of microorganisms associated with the fermenting process.[45] According to Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya:

Wine deludes the mind and a deluded person tends to forget piety; the person who forgets piety commits hiṃsā without hesitation.

Influence on vegetarian cuisines in India [edit]

The vegetarian cuisines of some regions of the Indian subcontinent accept been strongly influenced by Jainism. These include

- Gujarati Jain cuisine[47]

- Marwari Jain cuisine of Rajasthan

- Bundelkhandi Jain cuisine of central India

- Agrawal Jain cuisine of Delhi/Up

- Marathi Jain cuisine of South Maharashtra

- Jain Bunt cuisine of Karnataka

- Kannada Jains cuisine of Karnataka

- Tamil Jains cuisine of Northern Districts of Tamil Nadu.

In Republic of india, vegetarian food is considered appropriate for everyone for all occasions. This makes vegetarian restaurants quite popular. Many vegetarian restaurants and Mishtanna sugariness-shops – for case, the Ghantewala sweets of Delhi[48] and Jamna Mithya in Sagar – are run by Jains.

Some restaurants in India serve Jain versions of vegetarian dishes that leave out carrots, potatoes, onions and garlic. A few airlines serve Jain vegetarian dishes[49] [50] upon prior request.

According to survey responses of Indian Jains, 92% would be unwilling to eat at a restaurant that isn't exclusively vegetarian and 89% would be unwilling to eat at the domicile of a friend/acquaintance who isn't a vegetarian too.[16]

Historical groundwork [edit]

When Mahavira revived and reorganized the Jain community in the 6th century BCE, ahimsa was already an established, strictly observed rule.[51] [52] Parshvanatha, a tirthankara whom modern Western historians consider a historical effigy,[53] [54] lived in virtually the 8th century BCE[55] [56] and founded a community to which Mahavira's parents belonged.[57] [58] Parshvanatha'southward followers vowed to find ahimsa; this obligation was part of their caujjama dhamma (Fourfold Restraint).[59] [threescore] [61] [54]

In the times of Mahavira and in the post-obit centuries, Jains criticized Buddhists and followers of the Vedic faith or Hindus for negligence and inconsistency in the implementation of ahimsa. In item, they strongly objected to the Vedic tradition of animate being cede with subsequent meat-eating, and to hunting.[4] [62] [63] [64] [65] [66]

According to the famous Tamil classic, Tirukkuṛaḷ, which is also considered a Jain work by some scholars:

If the world did non purchase and eat meat, no ane would slaughter and offer meat for sale. (Kural 256)[67]

Some Brahmins—Kashmiri Pandits and Bengali Brahmins—accept traditionally eaten meat (primarily seafood). However, in regions with strong Jain influence such as Rajasthan and Gujarat, or strong Jain influence in the by such every bit Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, Brahmins are strict vegetarians. Bal Gangadhar Tilak has described Jainism every bit the originator of ahimsa. He wrote in a alphabetic character:

In ancient times, innumerable animals were butchered in sacrifices. Evidence in support of this is found in various poetic compositions such as the Meghaduta. Simply the credit for the disappearance of this terrible massacre from the Brahminical religion goes to Jainism.[68]

See also [edit]

- Fruitarianism

- Veganism

- Indian cuisine

- List of diets

- Sattvic diet

- Vegetarian cuisine

- Vegetarianism and religion

- Vitalism (Jainism)

- Vegetarianism and environmental

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 249.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 26–xxx.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 191–195.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Wiley 2006, p. 438.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Hemacandra, Yogashastra ii.31.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 154–160.

- ^ Jindal 1988, p. 74-xc.

- ^ Tähtinen 1976, p. 110.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 187–192.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 153–159.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1917, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Corichi, Manolo (8 July 2021). "Eight-in-x Indians limit meat in their diets, and four-in-10 consider themselves vegetarian". Pew Enquiry Middle . Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 166–169.

- ^ Tähtinen 1976, p. 37.

- ^ The Routledge handbook of faith and animal ethics. Linzey, Andrew. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN978-0-429-48984-vi. OCLC 1056109566.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Evans, Brett (2012). "Jainism's Intersection with Contemporary Upstanding Movements: An Ethnographic Test of a Diaspora Jain Community". Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography. 2 (ii): 21–32. doi:10.15273/jue.v2i2.8146. ISSN 2369-8721.

- ^ "Dairy farming and Hinsa (Cruelty)". Atmadrarma.com . Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ The Routledge handbook of organized religion and beast ideals. Linzey, Andrew. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN9780429489846. OCLC 1056109566.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Vijay G. Jain 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b "Mahavir Jayanti 2017: A beginner's a guide to Jain food", NDTV, ix April 2017

- ^ Jindal 1988, p. 89.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, p. 54.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, p. 180.

- ^ Sutrakrtangasutram 1.8.iii

- ^ Uttaradhyayanasutra 10

- ^ Tattvarthasutra vii.8

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Granoff 1992, pp. 32–35.

- ^ Sangave 1980, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b Tähtinen 1976, p. 109.

- ^ Lodha 1990, pp. 137–141.

- ^ Tähtinen 1976, p. 105.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 106.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Sangave 1980, p. 260.

- ^ Hemacandra: Yogashastra 3.37

- ^ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 86.

- ^ "Mahavir Jayanti 2015: The importance of a Satvik meal", NDTV, 2 April 2015, archived from the original on four April 2016

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 45.

- ^ "Catering to Jain palate". The Hindu. 30 June 2004. Archived from the original on 21 Nov 2004. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "A royal treat in Chandni Chowk", Hinduonnet.com, 7 November 2002, archived from the original on i March 2003

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Air Travel Vegetarian Fashion". Happycow.net . Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Dietary requirements". Emirates.com . Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Goyal 1987, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Chatterjee 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 19, 30.

- ^ a b Tähtinen 1976, p. 132.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Chatterjee 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Acaranga Sutra 2.15

- ^ Chatterjee 2000, pp. xx–21.

- ^ Sthananga Sutra 266

- ^ Goyal 1987, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Goyal 1987, p. 103.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 234.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 241.

- ^ Wiley 2006, p. 448.

- ^ Granoff 1992, pp. 1–43.

- ^ Tähtinen 1976, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Tiruvaḷḷuvar 2000.

- ^ Bombay Samachar, Mumbai:ten Dec, 1904

Sources [edit]

- Alsdorf, Ludwig (1962), Beiträge zur Geschichte von Vegetarismus und Rinderverehrung in Indien, Wiesbaden

- Chatterjee, Asim Kumar (2000), A comprehensive history of Jainism, vol. 1 (2nd rev. ed.), New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, ISBN81-215-0931-9

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (2nd ed.), London and New York Urban center: Routledge, ISBN0-415-26605-X

- Granoff, Phyllis (1992), "The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices", Journal of the International Clan of Buddhist Studies, 15

- Goyal, Śrīrāma (1987), A history of Indian Buddhism, Meerut: Kusumanjali Prakashan

- Jain, Champat Rai (1917), The Applied Path, The Central Jaina Publishing House

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - Jain, Jagdishchandra (1984), Life in Ancient India as Depicted in the Jain Canon and Commentaries (second ed.), New Delhi

- Jain, Vijay Chiliad. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN978-81-903639-iv-5

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - Jindal, Thousand.B. (1988), An epitome of Jainism, New Delhi

- Laidlaw, James (1995), Riches and Renunciation. Organized religion, economy, and society amid the Jains, Oxford

- Lodha, R.M. (1990), Conservation of Vegetation and Jain Philosophy, in: Medieval Jainism: Culture and Surround, New Delhi

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (1980), Jaina Community (2d ed.), Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN978-0-317-12346-3

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [Offset published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN81-208-1938-1

- Tähtinen, Unto (1976), Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London

- Tiruvaḷḷuvar (2000), Tirukkuṟaḷ (Tirukural : ethical masterpiece of the Tamil people), trans. Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, ISBN81-7017-390-6

- Wiley, Kristi Fifty. (2006), Flügel, Peter (ed.), Ahimsa and Compassion in Jainism, in Studies in Jaina History and Culture, London

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Jain vegetarianism at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Jain vegetarianism at Wikimedia Eatables - Listing of Foods that are not-Jain

devrieswhickeenet.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jain_vegetarianism

0 Response to "Chinese Religon That Doesnt Eat Beef"

Postar um comentário